Cryoablation ‘ice treatment’ works against large tumors

- Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in the world, with several treatment options available.

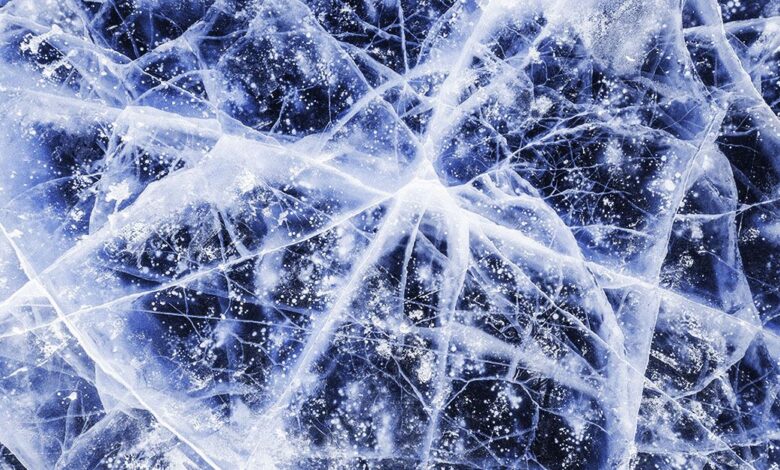

- A newer treatment called cryoablation, which uses extreme cold to kill cancer cells, has traditionally only been used to treat small breast cancer tumors.

- New research provides evidence that cryoablation may also be effective in treating large breast cancer tumors.

- The findings could offer an alternative to surgery for high risk breast cancer patients such as those with comorbidities.

With about

Depending on the type and stage of breast cancer, various treatment options are available, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery, and a newer treatment called cryoablation — a process that kills cancer tumors by freezing them.

According to a new study recently presented at the 2024 Society of Interventional Radiology Annual Scientific Meeting, most studies involving cryoablation and breast cancer have focused on treating small breast cancer tumors.

“Cryoablation has been typically used to treat tumors smaller than 1.5 cm,” Yolanda Bryce, MD, interventional radiologist at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York and co-author of this study told Medical News Today.

In this new research, Bryce and her team provide evidence suggesting cryoablation may also effectively treat large breast cancer tumors. The findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

This study involved 60 participants who all underwent cryoablation because they were not able to or did not want surgery.

“Traditionally, the standard of care for patients with breast cancer is to have surgery to remove the tumor — especially if the cancer is localized to the breast,” Bryce explained.

“But there are many patients who are not candidates for surgery. For instance, they may be older, have too many comorbidities that prohibit them from having surgery, or they’re on a blood thinner that they cannot come off of,” Bryce noted.

“Some comorbidities, such as heart disease or high blood pressure, can increase the risks associated with traditional surgical options,” she added.

“Cryoablation gives these patients another option to treat their cancer.”

According to Bryce, cryoablation is a minimally invasive treatment that uses imaging guidance such as ultrasound or a computed tomography (CT) scan to locate tumors.

“An interventional radiologist will then insert small, needle-like probes emitting extremely cold temperatures at the location of the tumor to create an ice ball that surrounds the tumor, killing the cancer cells,” she continued.

“When combined with

For this study, the cryoablation procedures were conducted with local anesthesia or minimal sedation. The procedure included a free-thaw cycle encompassing five to 10 minutes of freezing, 5 to 8 minutes of passive thaw, and another five to 10 minutes of freezing at 100% intensity. Participants were able to go home the same day after treatment.

Breast cancer tumor sizes amongst the study participants ranged in size from 0.3 to 9 cm with a 2.5 cm average size.

During cryoablation, participants with tumors larger than 1.4 cm were treated with one probe for each tumor centimeter.

When researchers followed up on study participants after a median period of 16 months, they found the recurrence rate was only 10%.

“Until now, cryoablation for breast cancer has been a treatment option for those with smaller tumors,” Bryce said.

“We didn’t know if it could be a feasible option for patients with larger tumors as well. For patients who have larger tumors but can’t undergo surgery, they would typically only be able to try radiation, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy to treat their tumors. But cryoablation could be more effective than this current standard of care for patients who are not surgical candidates,” Bryce continued.

“When treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, tumors will eventually return, so the fact that we saw only a 10% recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising. We will be conducting a retrospective study and will continue to watch this cohort of patients for further analysis. We hope that these results give those with breast cancer additional options to treat their cancer. The procedure is available to patients now, and we encourage all patients to discuss with their doctor which treatment option is best for their unique case.”

— Yolanda Bryce, MD, study co-author

After reviewing this study, Janie Grumley, MD, breast surgical oncologist and director of the Margie Petersen Breast Center at Providence Saint John’s Center and associate professor of surgery at Saint John’s Cancer Institute in Santa Monica, CA, told MNT that cryoablation is something doctors and scientists have been looking at for many years.

In general, Grumley said she does not come across many patients who are not eligible for surgery.

“There are patients who choose not to have surgery, but there aren’t a lot of patients who aren’t eligible for surgery — it’s pretty rare because surgical excision is a very small operation,” she explained. “If you do a lumpectomy, there’s very little risk to it, and you can even do it without full general anesthesia.”

Grumley also commented she felt the study was small with a very short follow-up.

“With breast cancer, doing a follow-up that is less than 10, 15, 20 years is really inadequate data,” she explained.

“I think there’s been only one large study, the ICE3 trial — when I say large is 197 patients. In the world of breast cancer, [194] patients is very small, but you need to see what’s the 10-year follow-up on these patients — what is their recurrence rate?”

“At

34 months in that study, the recurrence rate was already 2.1%, which is low, but probably still higher than those that underwent surgery,” Grumley continued. “So I think the jury’s still out and we have seen these patients in the community with really poor outcomes. So we really need to kind of wait and see what these long-term outcomes are.”— Janie Grumley, MD, breast surgical oncologist

Get Best News and Web Services here